This is a special article for me, as this one was written by my dear friend Matthew Miller. I know you will love what he has to say, he is a knowledgeable defender of our heritage. If you enjoy this piece, you can find it and other similar articles on his blog My Two Cents. I would also be remiss without making mention of his wonderful store confederateshop.com and all of the rare and out-of-print books that he has available. Without further ado, we proudly present the “Virginia Gentry” debut of Mr. Matthew Miller. — J.R. Dunmore

For too long we Southerners have allowed the attacks on our heroes to go on unanswered. Even when the attackers are reprimanded it is nothing more than a slap on the wrist. No longer will this be the case. While I am not a writer by profession, I have taken it upon myself to defend the life and legacy of perhaps our greatest hero here in writing. The fact is that many, if not all, major academics and mainstream historians of the past ten to fifteen years have attempted to dismantle history as it has been understood up until that point. Whether it was done for ideological reasons, personal vendettas against a false image of their perceived enemy, or to impress their peers with their glowing virtue in their willingness to destroy the memory of the “barbaric racist Southerners,” these people have fabricated awful tales and revived statements of attempted character assassination from as long ago as the 1860s.

I have the luxury of being an autodidact and therefore have not been compromised by “Righteous Cause” propaganda or peer pressure from these captured institutions. In my research, I’ve come across a claim that many modern academics make—something that has more and more recently been cited as truth—that Robert E. Lee was a cruel slave whipper. I’ve seen this declared in the Washington Post, referenced by the NPS, and taught as “fact” in so-called “respected academic circles.” It’s widely used to tar the reputation of one of America’s greatest Generals, Robert E. Lee, and seems to be the only allegedly “solid” claim to mar the reputation of the man. But is it true?

I am under the impression that the story itself caught much of its momentum in the early 2000s, particularly from Elizabeth Pryor’s 2007 book Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters. Pryor devotes an entire chapter—chapter 16— to this supposed occurrence. That being, Lee ordered and witnessed the brutal whipping of one of the Custis estate slaves named Mary Norris. She bases this on four pieces of evidence if you can call it that. Four newspaper pieces—two 1859 letters to the editor, an 1866 New York Tribune “statement from the lips of Norris” and an 1866 Cincinnati newspaper story (which could be classified as inadmissible hearsay). Three of those four pieces of evidence are even from anonymous sources.

I’ll say this. Anyone willing to bash the reputation of General Robert E. Lee better have their story straight, with concrete evidence to back up their claims. This is not intended to belittle a particular historian—I am simply referencing Elizabeth Pryor’s work because it’s the often-cited source of the lie about Lee. I entirely believe her position to be incorrect. She, like many other academics, has a narrative to uphold—and what better way to trash the South than by attacking our greatest hero?

The tall tale of Lee whipping his slaves is not factual and should never be considered as such. So, here are the six errors that are blatantly unanswered for in Reading the Man.

Pryor begins chapter 16 with a critical error. Her paramount piece of evidence, The Wesley Norris statement (Wesley was the brother of Mary Norris who supposedly gave the story), Pryor claims the account originated and was first given to an antislavery newspaper in 1866. This is incorrect. It was first published by the New York Tribune in March of 1866 (1) and thereafter spread through an anti-slavery paper called The National Anti-Slavery Standard newspaper which published the statement on April 16, 1866.

Mary is supposedly whipped. But studying deeper into the family, you learn there was an intricate relationship between her and her sister—and her sister and the Lees. Her sister, Selina, is a personal housekeeper of Mary Lee, Robert E. Lee’s wife. It’s objectively ridiculous that Selina and Mary Lee would be warm companions thereafter, especially if Mary Lee’s husband, Robert E. Lee had her sister brutally whipped. A trained researcher, such as Mrs. Pryor, should have at least mentioned a piece of the mountain of evidence that can be found on the intersecting relationships—factoring in greatly to the overall story

Pryor makes a huge blunder when she says “from the lips of [Wesley] Norris” that he “escaped” from Richmond to the Union lines, this is false. (2) Norris was free by Lee’s deed of manumission filed in Henrico Co. Courthouse on January 2, 1863, in which he then worked as a free man on the York River Railroad until September, when finally, Lee’s son Custis, gave him a pass which allowed him to ride through the Union lines. This is fact, as Maj. Gen. Meade’s correspondence confirms. (3)

Pryor claims in one of her footnotes that witnesses describe a whipping post at Arlington. This source comes from a 1975 publication sourcing an account of a Union soldier seeing a post on the property. (4) Furthermore, even if it did exist, it was not for the purpose of whipping Mary Norris—because her story goes that “Lee ordered [Norris] inside the barn, where they were tied firmly to posts,” as the “evidence” says.

Pryor claims all of this information on the whipping of Mary Norris is “corroborated by five witnesses” and is “substantiated by Lee’s own records.” Unsurprisingly, none of the witnesses are named. What she has are five supposed pieces of “evidence” to the episode. Digging deeper, two of the sources are anonymous letters to the editor of The New York Times published in June 1859. The third is not evidence, it's an unidentified person spoken of in the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper which simply says “[Lee] was the worst person I ever seen.” The fourth is an article from the Carroll County Democrat newspaper, published June 2, 1859—years before the Norris account even took place. The last could not be found in her footnotes.

This had me wondering if we could take all accounts as pieces of historical fact, like anonymous letters to the editor, I suppose Abraham Lincoln was really a homosexual? A shopkeeper named Joshua Fry Speed claims he shared a bed with Lincoln in 1837. So, based on this “evidence,” the universities can go ahead and begin teaching that Lincoln was a homosexual? (5) I digress…

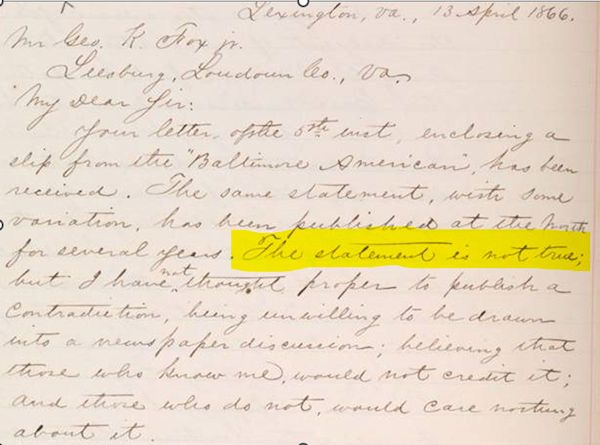

Finally, Pryor makes the biggest blunder of the chapter, that “Lee never completely denounced the story.” Once again—a false claim. There exists a letter that Robert E. Lee signed on April 13, 1866, replying to George K Fox, Jr., of the Loudoun Country Circuit Court, who wrote him to ask whether the story published in the press was true. Lee replied in the letter “…The statement is not true.” Here’s that letter: (6)

and

In the 473 pages of Reading the Man, not once does it give the reader a quote from either; a letter, diary, or memoir written by any member of the Lee family claiming a slave woman was ever abused at Arlington. Furthermore, nothing exists that would suggest Lee was cruel to any slave whatsoever.

A blogger, Joe Ryan, tells clearly how Mrs. Pryor, an academic professional, should have written her story: “an unidentified newspapers employee says an unidentified person told him that the person either personally witnessed, or was told by someone who claims to have personally witnessed, a whipping of a woman named Mary Norris.”(7)

One of the most common Lee quotes can be found in his private correspondence from 1854, where he said, “Slavery as an institution is a moral & political evil in any Country.” I recently heard a YouTube “historian” refute Lee’s quote by saying “Actions speak louder than words.” He’s right, actions do speak louder than words. Folks, there are literally books dedicated to the virtuous deeds of Robert E. Lee. Accounts that are irrefutable—from taking communion with a black man at a church service (while no one else would)—to giving water and kindness to wounded Yankee soldiers on the battlefield. (8)(9) The only thing these academics do when they attempt to spoil the good name of Robert E. Lee is to make themselves look like fools even more than they are.

So I would say, God bless the South and the name of Robert E. Lee.

I would like to thank Joe Ryan, a blogger and writer, as much of the research for this article was compiled by him. You can find it and similar work over on his blog. You can find it here, but be aware it is considered an unsecured link by Google.

Sources

New York Tribune, Vol. XXV, No. 7,789, March 26, 1866

Reading the Man, Elizabeth Pryor, 2007, pp.272-274

George Meade, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, September 6, 1863, 4pm, to Maj. Gen. H.W. Halleck, (War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, volume 29, part 2, pp. 158–159, Meade to Halleck, September 6, 1863, 4 p.m.)

Symbol, Sword, and Shield, Cooling, 1975, pp. 488, 491

https://nypost.com/2019/04/20/new-book-explores-abraham-lincolns-life-as-a-gay-man/

This letter, and an earlier one written to E.J. Quirk of San Francisco, in March 1866, is not the original. It is found in a letter book in the possession of the Virginia Historical Society that does contain entries in Lee’s hand, but this one is written in the hand of an unidentified person, probably a clerk at Washington College who helped Lee with his record-keeping. What foundation exists for it beyond this is found in the fact it was published, in 1874, in a book of his letters titled Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee, by the Rev. J. William Jones, D.D., formerly Chaplain Army Northern Virginia and of Washington College Virginia. – In the words of Joe Ryan, blogger

https://joeryancivilwar.com/Civil-War-Subjects/General-Lee-Slaves/General-Lee-Slave-Whipper.html

The Richmond Times Dispatch, April 16, 1905, Page 5, Image 21.

A Civil War Treasury of Tales, Benjamin Albert Botkin, 2000; Lee and the Wounded Union Soldier, p. 266, account from A.L. Long and Marcus J. Wright